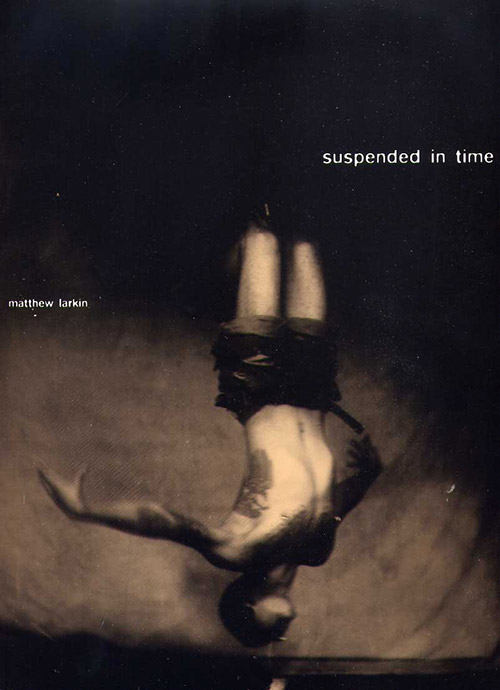

I recently stopped by wet plate collodion photographer Matthew Larkin’s studio and got a look at an advance copy of his just-published book, Suspended in Time, which is the end result of a two year collaboration between Larkin and body suspension group Rites of Passage.

I’m a bit of a hard sell when it comes to photography books. Not only had the images better be damn good, but it had better be printed well, form a coherent body of work, and the pictures mustn’t give everything up at once, they’ve got to be engaging and give me something to explore over time. A book I can flip through once and say, "that was good, but I got it, and I don’t necessarily need to see it again," isn’t getting my money or sustained attention. Suspended in Time delivers on all fronts, which is why it gets my vote and my cash. The photography—the subject of which will undoubtedly be truly challenging for some—is compelling and well edited, and the book itself is gorgeously designed by Binocular and impeccably printed by top-of-the-heap fine art printers Studley Press.

In the 15 or so years I’ve been doing print design professionally, I’ve developed an annoyingly critical eye that sees the slightest printing defect coming a mile away. Usually, offset printing is a frustrating guessing game, where getting the expected result is difficult, expensive, and rare, because it’s an analog, mechanical process where a lot can go wrong. Larkin and the designers were on press for a week working with the printers to get the duotone inks and varnish balanced just right. The result is nothing short of phenomenal; this is one of the best- and most interestingly-printed things I’ve ever seen.

What does this mean for the photos? They managed to get much, much closer to the look of the original black glass ambrotypes than I thought was possible with offset printing. Due to the colored varnish, the page surfaces are half-way between matte and high-gloss. It’s a look that I ordinarily wouldn’t care for, but it happens to work perfectly for the material: some of the otherworldliness of the glass originals is of course lost on paper, but the finish makes up for it, albeit in a slightly different, though no less effective, direction.

There are few cues about when the photos were made, which makes them difficult to nail down. They’re equally believable at 1 or 150 years old. The printing makes them look both immediate and anachronistic, with none of the sense of temporal distance that usually comes with old photos. Time-wise, they pick you up and throw you, but don’t let you see where you landed. It’s a neat trick that sets the stage for beginning the real work of digesting the content.

I think you should really have your own experience of the photos, so I’m not going to say anything more about the subjects. I do suggest going for the ride, though, and looking at and thinking about what comes up for you when you look at them. It’s probably going to be a challenge, but I think it’s a worthy one. There are a lot of interesting questions to be found here if you let them in. If you’d like to get a peek, there are several plates from the book here at the publisher’s site and in this previous post here on Photon Detector.

Given the material, the photographic process, and the fact that this is the first book of its kind, Larkin had an opportunity to write a Weston daybook-style flowery and self-congratulatory bit of wankery for the introduction. I’m quite pleased to report that he didn’t take it. Instead, he provides enough background to help you understand what you’re looking at, but stops before boring you or turning it into a public masturbation session, and lets the work speak for itself. A successful artist statement is a rare treat. Thanks for that.

Don’t let the fact that I know Larkin detract from this statement in any way: this book is incredible. It’s a unique piece that I know I’ll get a lot of exploration out of for a long time to come. I almost tried to come up with something bad to say so this seems more balanced, but I’ve got nothing. (For the record, I don’t accept free or discounted stuff from anyone I write about here. I saw the book, I like it, and I’m paying full price.)

You can order direct from the publisher, Black Barn Editions. The book is US $70 plus shipping, and express and international shipping are available.

Look for interviews with Larkin and several of the subjects in the coming weeks.

Clothbound with jacket, 9.25 × 11.5 inches

70 duotone illustrations in 144 pages

Edition limited to 2000, of which 100 are signed and numbered by the artist.

ISBN 978-0-9793352-0-4

US $70.00

More coverage

Review by NYC.com

Cover image © copyright 2007 Black Barn Editions. Used with permission.